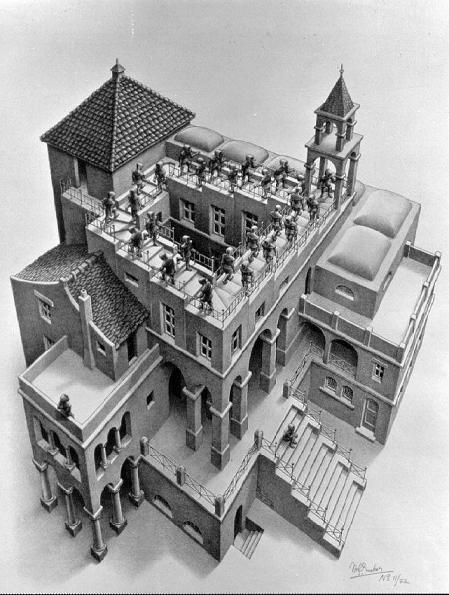

Ascending and Descending, M. C. Escher

‘Tis an establish’d maxim in metaphysics, That whatever the mind clearly conceives, includes the idea of possible existence, or in other words, that nothing we imagine is absolutely impossible. We can form the idea of a golden mountain, and from thence conclude that such a mountain may actually exist. We can form no idea of a mountain without a valley, and therefore regard it as impossible.

Now ‘tis certain we have an idea of extension; for otherwise why do we talk and reason concerning it?

— David Hume, A Treatise of Human Nature I.ii

For they practically accept the general consciousness, which testifies to the existence of an external world, and being at the same time anxious to refute it they speak of the external things as “like something external.” If they did not themselves at the bottom acknowledge the existence of the external world, how could they use the expression “like something external?” No one says, “Vishnumitra appears like the son of a barren mother.”

— Śaṃkara, Brahmasūtrabhāṣya II.ii.28

In the history of philosophy, it is not unusual for multiple thinkers to use different means to reach the same conclusion or to use the same means to reach different conclusions. In the passages cited above, Hume and Śaṃkara, though separated by a thousand years and half a world, seem to suggest similar very similar “metaphysical maxims” for use as a basis of argument. Hume uses the principle that anything which is conceivable is possible to argue for the extension of space (and against its infinite divisibility)†Interestingly, Hume seems to unintentionally use the converse of the principle given by arguing that infinitely divisible space is impossible because it is inconceivable. This principle (¬ClearlyConceives(x) → ¬◊x) is also sometimes defended but is logically independent from the one he gives above., whereas Śaṃkara uses a similar principle to argue against the Yogācāra denial of the external world. Nevertheless, there are important differences between Hume and Śaṃkara. The principle Śaṃkara is arguing from is not only that conceivability is linked to possibility, but also that nothing appears like what is impossible. The difference can be formalized by casting Hume’s claim as ClearlyConceives(x) → ◊x, and Śaṃkara’s as ¬(AppearsAs(x) ∧ ¬◊x) or its equivalents, AppearsAs(x) → ◊x and ¬◊x → ¬AppearsAs(x).

An interesting aspect of Śaṃkara’s version of Advaita Vedānta is his repeated emphasis on the vanity of idle philosophical speculation and the importance of a commonsensical view of the world. For instance, he writes,

Whenever (to add a general reflexion) something perfectly well known from ordinary experience is not admitted by philosophers, they may indeed establish their own view and demolish the contrary opinion by means of words, but they thereby neither convince others nor even themselves. Whatever has been ascertained to be such and such must also be represented as such and such; attempts to represent it as something else prove nothing but the vain talkativeness of those who make those attempts.†Brahmasūtrabhāṣya, II.ii.25.

Yet, at the same time, Śaṃkara holds to the title claim of Advaita, namely the non-duality of self and Brahman: “Thou art that.” This claim seems to be a deeply counterintuitive and non-commonsensical claim about the nature of the self. How could I be mistaken about the nature of my own self? As Śaṃkara himself writes in order to attack the claims of those who hold a no-self view, “the conscious subject never has any doubt whether it is itself or only similar to itself.”†Ibid. If I know my self, why should I not already recognize myself as Brahman? As Śaṃkara has his rhetorical opponent exclaim, “if Brahman is generally known as the Self, there is no room for an enquiry into it!” To which he gives the answer, “Not so, we reply; for there is a conflict of opinions as to its special nature.”†Ibid., I.i.1.

This paper will explore the place of Śaṃkara’s maxim in Advaita Vedānta by first noting some seeming counter-examples of the maxim then determining what sort of modality is needed to keep the claims made by Śaṃkara plausible. On this basis, an apparent contradiction between Śaṃkara’s maxim and the non-duality of the self will be demonstrated and defused through an explanation of Śaṃkara’s epistemological and metaphysical commitments.

If we take Śaṃkara as arguing from the empirical claim that no one interprets her perceptions as an instantiated impossible situation, then it is natural to look for counter-examples to that claim, in which one looks at the world and does mistake an actual situation for an impossible one. One possible case of this might be optical illusions and the drawings of M. C. Escher. These pictures involve the compounding of picture elements in such a way as to make a scene that the mind either cannot interpret with any consistency (as in the case of the Necker cube) or can interpret but instinctively offers imaginative resistance to, such as Escher’s Ascending and Descending, pictured above. Graham Priest in “Perceiving Contradictions” argues that such figures, among other things, are contradictions but can nevertheless be perceived as such, which would seem to settle the empirical question — Priest at least might mistake Vishnumitra for the son of a barren mother — except that Priest also believes that contradictions are (sometimes) possible, which means that Priest can assent without contradiction (though it is not clear that such would necessarily be an obstacle to Priest) to both Śaṃkara’s maxim that everything appears as something possible and to the proposition that some optical illusions are perceivable contradictions. Thus, while Priest might mistake Vishnumitra for the son of a barren mother, this would only occur in the case that Priest thinks it possible to be son of a barren mother.

On the other hand, when Śaṃkara applied his maxim, he could not have meant that no one ever mistakenly thinks that something which is impossible is possible, since that is the sort of error that he accuses his opponents of from time to time. Indeed, this would make teaching a logic class much simpler, since one need only be able to perceive the equation in the right manner to be guaranteed of its correctness. Similarly, in an idle moment, though I have been told that Alice is barren, I may come to think that perhaps she is Vishnumitra’s mother because of their resemblance — at least until I actively remember that she is barren. Unless Śaṃkara holds the position that words which refer to the impossible are strictly nonsense, then it cannot be enough for a picture to make us consider the existence of the impossible, since by analogy the words “son of a barren mother” are intelligible because its parts are intelligible, but as a whole phrase, it fails to refer to anything, since it is impossible.†The strategy for dealing with “the rabbit’s horn” in Nyāya is to break into parts with real referents, according to Perrett in “Is Whatever Exists Knowable and Nameable?” p. 317. Presumably, Śaṃkara would also accepts such a strategy. In the same way, a picture that merely referred to the impossible, like a picture the contents of which were a series of symbols representing a ≠ a would also present no challenge to Śaṃkara’s maxim. The only way a challenge could come from an image would be if the content of image itself were enough to cause one to perceive what appears as the impossible. Roy Sorensen in “Art of the Impossible” offers a $100 prize to anyone who can produce such an image that “perceptually depicts a logical falsehood” and preemptively rejects many possible contenders for the prize such as optical illusions and other inventive incongruities on the grounds that the images are not themselves truly contradictions in perception. Like a negligent logic student, they bring together parts which are plausible in isolation but dissolve under the scrutiny caused by the absurdity of their totality. As M. J. Cresswell explains in “A Highly Impossible Scene,” “In the impossible picture case, parts of the picture are perfectly consistent but they contradict other parts of the picture.”†Cresswell, p. 70.

Accordingly, we might propose scaling Śaṃkara’s maxim back on the model of Hume’s, in which to be clearly conceivable is to be possible, and, if we wish to reject dialetheism, dispute that Priest is really able to clearly perceive the contradictions in the various illusions he offers in “Perceiving Contradictions” and elsewhere. Take an example provided by William Boardman in “Dreams, Dramas, and Scepticism”:

a character in a dream, or one in a play, might succeed even in squaring the circle. Since, of course, one cannot intelligibly imagine a circle’s being squared, one’s dream is not likely to focus on the details of how the feat was accomplished. All that is needed is for various pieces of the story to fit together in the way they might in actual life […] Moreover, even the details of how the circle was squared might be dreamt. Though they will not in actuality constitute a recipe for squaring the circle yet within the dream they may be a complete recipe for squaring the circle. For to dream of someone’s squaring the circle is to dream of something which, in the dream, is acknowledged by all to have been the squaring of the circle.†Boardman, pp. 224–225.

While a dream about squaring the circle may possess many of the elements that one would take to be the constituents of the act, they cannot contain a coherent combination of those elements, since it has been shown mathematically to be impossible to square the circle. Since as part of a dream, one naturally lowers one’s standards for clarity and coherence, one does not notice that the elements fail to join into a coherent whole, and one may mistake an invalid proof for a valid one, but this does not challenge the fact that it is impossible to clearly and distinctly comprehend the whole of an invalid proof. Indeed, even in our waking state, we may accidentally mistake an invalid proof for a valid one, or vice-versa, but this is surely the fault of inattention to the details rather than an assent to a thoroughly understood contradiction. We may allow that AppearsAs(p) ∧ AppearsAs(¬p), but we will nevertheless insist that ¬ClearlyAppearsAs(p ∧ ¬p) since ¬◊(p ∧ ¬p).

In the particular case of the argument against the Yogācāra, Śaṃkara might claim that our perception of there being an external world is so coherent that it cannot be a merely temporary lapse or relaxation of our standards that causes us to believe in it. Even in cases like dreams where we imagine ourselves as perceiving an external world, when we are not in fact perceiving an external world, do not challenge the existence of the external world as something that is otherwise possible if not at that time actual. As Śaṃkara explains about dreams,

It is not true that the world of dreams is real; it is mere illusion and there is not a particle of reality in it. — Why? — ”On account of its nature not manifesting itself with the totality,” i.e. because the nature of the dream world does not manifest itself with the totality of the attributes of real things. — What then do you mean by the “totality”? — The fulfilment of the conditions of place, time, and cause, and the circumstance of non-refutation. All these have their sphere in real things, but cannot be applied to dreams.†Brahmasūtrabhāṣya, III.ii.3.

Hence for Śaṃkara, the “totality” of experience plays a role similar to that of the “clarity” of an idea for Hume. If, for example, one were to examine Ascending and Descending, it may appear like a circuit of stairs that continues to rise (or descend) without end in defiance of geometric possibility, but it only appears as such to an unsteady gaze, which is a sign that our future perception of the image will never achieve the “totality” that is necessary for a proper perception by which judgments about possibility can be made. Śaṃkara’s criterion of totality is not quite the same as the criterion of clarity, since clarity in perception is a kind of gestalt, but what Śaṃkara is arguing is that attempts to interpret the drawing as though it were an endless staircase will lead to frustration in some future interaction, when it is revealed not to be. It can be formulated as ¬(CoherentlyAppearsAs(x) ∧ ¬◊x). Nevertheless, that we instinctively reject the image as lacking gestalt now is a sign of its destiny of being contradicted later. However, it might be objected that Śaṃkara is only shifting his burden from showing that something is possible or not as such to showing that its perception is so stable as to guarantee its possibility (or, if we can presume to use the maxim’s converse, so unstable as to guarantee impossibility), in which case the Yogācārins might argue that both the external world and the Advaitin conception of the self are similarly lacking in totality and doomed to eventual rejection as impossible. Accordingly, before examining whether Śaṃkara’s seemingly counter-intuitive conception of the self runs afoul of his own maxim, we must examine what the words “possibility” and “impossibility” could mean in his metaphysical system, in order to tell when and where the mark of totality can be found.

In the Brahmasūtrabhāṣya, Śaṃkara straightforwardly explains to his Yogācārin opponent why the defense of their doctrine by means of arguments for the impossibility of external world must fail, given the nature of possibility itself:

But — the Bauddha may reply — we conclude that the object of perception is only like something external because external things are impossible. — This conclusion we rejoin is improper, since the possibility or impossibility of things is to be determined only on the ground of the operation or non-operation of the means of right knowledge; while on the other hand, the operation and non-operation of the means of right knowledge are not to be made dependent on preconceived possibilities or impossibilities. Possible is whatever is apprehended by perception or some other means of proof; impossible is what is not so apprehended.†Ibid., II.ii.28. Emphasis mine.

As in other classical schools of Indian thought, Advaita Vedānta holds that it is “the means of right knowledge,” or pramāṇa, by which we come to know the world. The pramāṇas accepted by Advaitins are perception, inference, testimony, comparison, non-cognition, and postulation, though Śaṃkara himself refers to only the first three in his works.†Deutsch, p. 69. In either case, Śaṃkara seems to be arguing for a metaphysics in which ontology follows after epistemology. Note the seemingly anti-realist tenor of this criticism of the Yogācārins:

you maintain thereby that ideas exist which are not apprehended by any of the means of knowledge, and which are without a knowing being; which is no better than to assert that a thousand lamps burning inside some impenetrable mass of rocks manifest themselves.†Brahmasūtrabhāṣya., II.ii.28.

Ideas without at least the potential for being known by some means (be it inference or testimony if not perception) cannot be considered to really exist. If they did exist, then they should have some effect on the world from which they could, at least in principle, be inferred. This is not to say Śaṃkara truly was an anti-realist or that he thought existence ultimately depends on knowability, just that he believes in the in-principle knowability of all existing things. In “Dreams and Reality,” Chakravarthi Ram-Prasad summarizes the meaning of “exists” for Advaita:

For the Advaitin, if an object “‘really’ exists”, that means something like that it is “proved that the object would have to exist if the experience of it is to possess the features that it (the experience of that object) does.”†“Dream and Reality,” p. 438.

Elsewhere, Ram-Prasad labels Śaṃkara a “non-realist” as opposed to an anti-realist. No matter his exact designation however, because of their definition of existence, the school of Advaita Vedānta has traditionally been classified as having a theory of intrinsic truth-apprehension (svataḥprāmāṇyavāda) according to which being true does not depend on anything other than being rightly perceived.†Perrett, “Conceptions of Indian Philosophy,” p. 26, Deutsch, p. 86, et al.

With this epistemological background in place, let us return to the question of what is possible. Under the definition of possible as “whatever is apprehended,” the definition of existent as possible to be known, and the definition of truth as being rightly perceived, it might appear that there is no way left for possibility to be different from actuality (and impossibility from non-actuality).

Corroborating this conjecture is the fact that a difference between logical impossibility and merely being unexampled was not always maintained in classical Indian thought. For example, note this observation made by Arindam Chakrabarti about Nyāya:

Notwithstanding extremely sophisticated distinctions between self-contradictions (such as the liar-sentence) and pragmatic self-refuation (like “I am not aware of this”), the Naiyāyikas use “barren woman’s son” and “horn of a rabbit” as empty terms without distinction.†“Rationality in Indian Philosophy,” pp. 270–1.

In this case, we can see that the Indians made no distinction between the impossibility of a logical contradiction (in the case of the son of a barren mother) and the mere lack of actuality in an uninstantiated class (like rabbits that have horns†One might make the case that a rabbits with a horn is also a logical impossibility on the grounds that such an animal would not be a true rabbit, but only a rabbit-like creature, perhaps a jackalope, but this defense appears not have been attempted, and at any rate, other forms of impossibility will be needed later in our account. See also Matilal’s white crow, p. 129 and his p. 151 n. 1.). Chakrabarti follows Mohanty in speculating that this is caused in part because for Indian logicians, “Soundness was more important than mere validity.”†“Rationality in Indian Philosophy,” p. 271. No matter what the cause, the effect would seem to be that whatever does not happen to exist ought to be counted by Indian thinkers as being impossible. On the other hand, Paul Williams in “On the Abhidharma Ontology” gives evidence that for the early Madhyamaka, the rabbit’s horn was “merely an unexampled term the occurrence of which was not actually a logical contradiction.”†Williams, p. 233. Be that as it may, as Bimal Matilal notes in Logical and Ethical Issues of Religious Belief,

Possibility as a modal notion had very limited use in the whole of Indian philosophy. Most possibilities are simply future contingencies, or a possibility that has already been excluded or nullified by a contingency.†Matilal, p. 150.

Accordingly, we may need to develop a novel interpretation of Śaṃkara’s notion of possibility if we run in to difficulties in its application.

To return to the issue of Śaṃkara’s maxim, we want to interpret the maxim so that it is most plausible, but if there is absolutely no distinction made between actual and possible and not actual and impossible, then seeming incongruities will result. One such incongruity is the collapse of all impossibilities into one another. As Cresswell explains an example of Bertrand Russell’s, “the class of Chinese Popes and the class of golden mountains […] are extensionally equivalent. But clearly they do not have the same meaning.”†Cresswell, p. 70. Cresswell then suggests two ways of differentiating the two: in terms of their simple parts or in terms of their possibility for fulfillment. We have already seen that in the case of the phrase “son of a barren mother” the parts of the phrase individual refer but fail to cohere as a totality, like an optical illusion. In the same way, the phrase “my blue car” has parts that refer and we would not ordinarily find anything impossible in the phrase, but as Matilal writes,

Suppose my car is red. This fact, a contingent fact, has already defeated (excluded) the possibility of its being not-red. Does the “excluded” possibility, then, join the group of impossibilities? No clear and explicit answer emerges from the Indian philosophers except in their discussion ([eg. by the later Naiyāyika] Udayana) of naming the non-existent or citing a non-existent entity as an example.†Matilal, p. 150.

Though the phrase “my blue car” has no extensional content, we may want to preserve a distinction between this mere non-actuality and full impossibility, particularly since preserving this distinction will prove helpful for making sense of the pramāṇa of “non-cognition” employed by Advaita Vedānta and others. In non-cognition one “sees” the absence of something by noticing that it is not observed. Cresswell gives a contemporary example that may be taken to be an instance of non-cognition:

[W]hen the witness is shown the police files, his answer that the bank robber was none of those, gives information to the police; even if not as much as if his answer had been “yes” to one of the photographs. So although the negation of a photograph cannot itself be a photograph, yet a photograph can be used to say: things are not like that. We can therefore speak of the negation of a photograph and its nature is quite simple. It is simply the set of worlds not realized by the photograph.†Cresswell, p. 77.

Hence, on Cresswell’s explanation, the pramāṇa of non-cognition would operate on the recognition of the difference between the actual world and a set of possible worlds that contain the object the absence of which is noticed, which means that we don’t want to treat my blue car as an impossible object with recognizable parts, but as a possible object that happens not to be actual. This gives us one reason for attempting to refine Śaṃkara’s treatment of possibility, namely that without a sense of possibility that is broader than mere actuality, non-cognition would be noticing the absence of an impossible object, which might present difficulties under Śaṃkara’s maxim.

Another reason to refine the notion of impossibility is that if what is not the case is impossible, then, on Śaṃkara’s maxim, perception should never go wrong, since that would be a case of inferring an impossibility from perception. However, perception clearly does go wrong. As Śaṃkara admits “sometimes with regard to an external thing a doubt may arise whether it is that or merely is similar to that; for mistakes may be made concerning what lies outside our minds.”†Brahmasūtrabhāṣya, II.ii.25.

Of course, we have already limited the maxim to “coherently appearing as,” which it might be argued, as the right perception, perception of totality, can never goes wrong. The difficulty with this is that is merely tautological: what makes a perception right is that it hasn’t gone wrong. This might be interpreted as strengthening the general acceptability of Śaṃkara’s maxim (since it is now merely tautological to say that in right perception one perceives rightly), but this raises the question of whether the principle so interpreted would be strong enough to do the work of refuting the Yogācārans. If the meaning of “right perception” strays too far from the realm of common sense, then it becomes an object of dispute instead of the grounds of dispute. If Śaṃkara insists that we correctly perceive an external world, self, etc. then the Yogācārans may insist that we do not, and the dispute will end at an impasse. It would be better for Śaṃkara if his maxim is a (compelling) axiomatic claim and not a logical truth, so that Śaṃkara can get his opponent to concede that our perception of an external world is a totality. If he claims instead that it is a right perception, his opponent will not assent to the premise. Hence, it is no surprise to find that Śaṃkara does admit that “perception” goes wrong:

For instance, the ignorant think of fire-fly as fire, or of the sky as blue surface; these are perceptions no doubt, but when the evidence of the other means of knowledge regarding them has been definitely known to be true, the perceptions of the ignorant, though they are definite experiences, prove to be fallacious.†Bṛhadāraṇyakopaniṣadbhāṣya, III.iii.1, p. 459.

As such, we may wish to refine Śaṃkara’s treatment of impossibility, through the use of what Arthur Prior has dubbed “Diodoran modality.” According to Prior,

The Megaric logician Diodorus defined the possible as that which either is or at some time will be true, the impossible as that which neither is nor ever will be true, and the necessary as that which both is and always will be true. These definitions assume — as ancient and medieval logic generally assumes — that the same proposition may be true at one time and false at another; Dr. Benson Mates has accordingly remarked, in his recent study of Stoic logic, that Diodoran “propositions” are not “propositions” in the modern sense, but something more like propositional functions, and he represents them as such in his symbolic treatment of the Diodoran definitions of the modal operators.†Prior, p. 205.

This view of possibility has the advantage of cohering reasonably well with Śaṃkara definition of possible as “whatever is apprehended by perception or some other means of proof” (since one must merely insert the qualifying clause “at some time”), while at the same time allowing for a notion of possibility that can handle the case of non-cognition (at a prior time one saw the face of the thief, so it is a possibility, and what one now notes to the police is its current absence) and making the idea of mistaken perception more understandable as a case of perceiving what is it is possible to perceive at other times. We can formalize it as AtSomeTime(x) ↔ ◊x, which gives us necessity as ¬AtSomeTime(¬x) ↔ □x. To see whether it is fully capable of doing the work that Śaṃkara needs it to do, we must examine the effect of this notion of possibility on the acceptability of Śaṃkara’s maxim in the larger context of his other theories.

It is difficult to give general principles for deciding whether to adopt a particular “metaphysical maxim,” due to the inherent circularity in the attempt at justifying such a maxim, but some of the key considerations must be coherence, practicality, and (of course) truth. The third criterion is of course the most important but also the most difficult to judge, so in this paper, I will consider only the first two and (further limiting my scope), I shall focus primarily on the implication of the maxim for the coherence and practicality of the doctrine of the self in Advaita Vedānta.

To begin our investigation into the self of Śaṃkara, we must provide the background in which to present his theory of self. Unlike the Buddhists, Śaṃkara takes the denial of the existence of the self to be self-refuting. This conclusion is compatible with the maxim, since it appears to me that I have something like a self hence it is possible that I do, but Śaṃkara goes beyond that and argues for the existence of the self with an argument that has been likened†Deutsch, p. 50, et al. to the cogito. Śaṃkara argues that a refutation of the self is impossible, since it is the existence of the self which allows the working of the pramāṇa that are to establish the self’s existence:

But the Self, as being the abode of the energy that acts through the means of right knowledge, is itself established previously to that energy. And to refute such a self-established entity is impossible. An adventitious thing, indeed, may be refuted, but not that which is the essential nature (of him who attempts the refutation); for it is the essential nature of him who refutes.†Brahmasūtrabhāṣya, II.iii.7.

However, it remains to be seen if what Śaṃkara means by “self” and what I mean by “self” when I say “it appears to me that I have something like a self” are the same thing. Even the most abstruse thinker can take up the mantle of common sense if allowed to define what it is that common sense terms mean. To return to our early quote of Śaṃkara, if “there is a conflict of opinions as to its special nature,” what does he take that special nature to be? As he goes on to state, “the Lord is the Self of the enjoyer,” that is, there is only one self and that self is Brahman.†Ibid., I.i.1. However, to be clear here, we need to make a distinction between the terms ātman and jīva, both of which might plausibly be translated as “self.” Though the word ātman has the non-technical meaning of “self” in Sanskrit, in Advaita Vedānta, it has the specific meaning of the eternal, purely conscious self, which they maintain to be one. Jīva, on the other hand, refers to the individual self. But as Eliot Deutsch points out, the cogito given above “does not so much prove the Ātman as it does the jīva — the jīva, which has the kind of self-consciousness described in, and presumed by, the argument, and not the Ātman, which is pure consciousness.”†Deutsch, p. 51. However, Śaṃkara has already anticipated this objection and invites it, since the oneness of the self and Brahman is not a matter to be proven by argument, but a matter of proper exegesis of the Vedas.

In matters to be known from Scripture mere reasoning is not to be relied on for the following reason also. As the thoughts of man are altogether unfettered, reasoning which disregards the holy texts and rests on individual opinion only has no proper foundation. We see how arguments, which some clever men had excogitated with great pains, are shown, by people still more ingenious, to be fallacious, and how the arguments of the latter again are refuted in their turn by other men; so that, on account of the diversity of men’s opinions, it is impossible to accept mere reasoning as having a sure foundation. […] The Veda, on the other hand, which is eternal and the source of knowledge, may be allowed to have for its object firmly established things, and hence the perfection of that knowledge which is founded on the Veda cannot be denied by any of the logicians of the past, present, or future. […] Our final position therefore is, that on the ground of Scripture and of reasoning subordinate to Scripture, the intelligent Brahman is to be considered the cause and substance of the world.†Brahmasūtrabhāṣya, II.i.11.

Hence, the ultimate reason for Śaṃkara’s claim of the non-duality of the self is his exegesis of the scriptures,†The particular exegetical claim that the scriptures promote the non-dualist view can be seen in various forms in many places. In particular, see Brahmasūtrabhāṣya, II.i.21, “For Scripture declares the other, i.e. the embodied soul, to be one with Brahman, as is shown by the passage, ‘That is the Self; that art thou…” since any merely intellectual argument is subject to contradiction by some other intellectual argument. That these arguments contradict each other does not leave us completely ignorant however. That they exist at all is proof that there must be something behind reality about which some or all of the arguments are mistaken. The oneness of the self is the reason that the various pramāṇas work, but it is not subject to illumination by anything other than itself.†Brahmasūtrabhāṣya, I.iii.22, “Brahman as self-luminous is not perceived by means of any other light. Brahman manifests everything else, but is not manifested by anything else.” Hence, we can see that the concept of contradiction provides an important negative and positive regulative role in Śaṃkara’s thought: negatively, it warns us against trusting any one argument, but positively, it tells us that there is a fact of the matter about which we are mistaken which we must clarify by means of a more reliable source, i.e., the Vedas. Śaṃkara’s task is similar to Kant’s quest “to annul knowledge in order to make room for faith,”†Kant, Bxxx. except that the way that Śaṃkara uses the term “faith” to describe the liberation achievable through the Vedas is significantly different from how Kant uses the term.†Cf. Bṛhadāraṇyakopaniṣadbhāṣya, II.i.1, p. 254, “That faith is a great factor in the realization of Brahman is another implication of the story…”

In order to understand how it is possible for the self to be non-dual, as Śaṃkara takes the Vedas to claim, we need to understand the doctrine of adhyāsa or superimposition that underlies this view about the positive and negative role of contradiction. Suppose one mistakes a rope for a snake:

Whenever we deny something unreal, we do so with reference to something real; the unreal snake, e.g. is negatived with reference to the real rope. But this (denial of something unreal with reference to something real) is possible only if some entity is left. If everything is denied, no entity is left, and if no entity is left, the denial of some other entity which we may wish to undertake, becomes impossible, i.e. that latter entity becomes real and as such cannot be negatived.†Brahmasūtrabhāṣya, III.ii.22.

All aspects of ordinary existence are subject to negation with respect to some other experience. However, there must be something behind the experience which is the cause of the real thing that is obscured by the mistake, just as the rope is the basis for the mistaken perception of the snake. Every illusion is taken as having a basis in the real that is misunderstood through ignorance, which is how ordinary people are able to mistake fireflies for fire and so on. As Roy Perrett explains in “Truth, Relativism, and Western Conceptions of Indian Philosophy,” this theory in conjunction with the Advaita theory of truth has important effects on what it is that Advaitins count as being true:

Advaita [identifies] truth with uncontradictedness (abādhitatva), where this is understood to mean the property of never being contradicted. However, as Advaita recognizes, an implication of this is that only the knowledge of Brahman as ultimate reality is true and no empirical knowledge is ever ultimately true.†“Conceptions of Indian Philosophy,” p. 27.

Here we see the other analogy of Śaṃkara to Kant: both attempt to show something about the nature of the ultimate through the refutation of various attempts to identify it with any object of experience, while at the same time, attempting to defend a kind of direct realism about the application of the sense to matters of ordinary experience. Chakrabarti describes Śaṃkara as “distinguishing the practical and noumenal level”†“Metaphysics in India,” p. 321. and summarizes his position thusly:

Śaṃkara, while rejecting subjective idealism, takes up the Upanisadic idea that only the ever-present and the changeless must be real. Being lumpy or shaped as a cup or pulverized are states which come and go (like the illusory mirage-water) whereas clay — the generic stuff — remains ever present. The only ever present stuff ultimately is pure consciousness (which is not to be confused with someone or someone’s awareness of something). The plurality and objecthood displayed by the world are neither as real as this ever unnegated consciousness which is called brahman (All) or ātman (self) nor as unreal as an unpresentable impossibility. It is a presented falsehood or māyā which literally means magic.†Ibid., p. 322.

The illusion of māyā has seduced our senses with ignorance. Nevertheless, this error is also a vital intellectual resource:

The mutual superimposition of the Self and the Non-Self, which is termed Nescience, is the presupposition on which there base all the practical distinctions — those made in ordinary life as well as those laid down by the Veda — between means of knowledge, objects of knowledge (and knowing persons), and all scriptural texts, whether they are concerned with injunctions and prohibitions (of meritorious and non-meritorious actions), or with final release. — But how can the means of right knowledge such as perception, inference, &c., and scriptural texts have for their object that which is dependent on Nescience? — Because, we reply, the means of right knowledge cannot operate unless there be a knowing personality, and because the existence of the latter depends on the erroneous notion that the body, the senses, and so on, are identical with, or belong to, the Self of the knowing person.†Brahmasūtrabhāṣya, I.i.1.

Thus, it is by means of our primal ignorance that the self identifies itself with the body, and then comes to learn about the means of practically getting around in the world.†To be clear, there is a dispute within later Advaita about whether the ignorance is of the jīva or of Brahman, but Śaṃkara apparently has not left us enough evidence to clearly determine his position on the question. Nevertheless, inferring that our bodies are our selves, though of pragmatic value, is not only “the cause of all evil”†Ibid. but a mistake:

It is a well-ascertained truth that that notion of identity of the individual Self with the not-Self, — with the physical body and the like — which is common to all physical creatures is caused by avidyā [ignorance], just as a pillar (in the darkness) is mistaken (through avidyā) for a human being. But thereby no essential quality of the man is actually transfered to the pillar, nor is any essential quality of the pillar transfered to the man. Similarly, consciousness never actually pertains to the body; neither can it be that any attributes of the body — such as pleasure, pain, and dullness — actually pertain to Consciousness, to the Self; for, like decay and death, such attributes are ascribed to the Self through avidyā.†Bhagavadgītābhāṣya, XIII, 2.

Hence our true selves do not have any of the properties we commonly take ourselves as having except for its inherent properties of consciousness and enjoyment. Yet, it appears that this contradicts the maxim on Diodoran grounds. Since there was never a time when our selves were non-enjoyers and there never will be, we are justified, under a Diodoran modality, in concluding that it is impossible for the self to be a non-enjoyer. However, it sometimes appears to us that the self is sad or happy or whatever. But on the maxim, no one mistakenly infers the impossible. Formally, the argument can be given as:

1. CoherentlyAppearsAs(I am sad) from a particular experience

2. ¬AtSomeTime(I am sad) from the Vedas

3. CoherentlyAppearsAs(I am sad) → ◊(I am sad) from Śaṃkara’s maxim

4. ¬AtSomeTime(I am sad) → ¬◊(I am sad) from Diodoran modality

5. Contradiction: ◊(I am sad) and ¬◊(I am sad) from 1 & 3 and from 2 & 4

Hence, we must deny at least one premise in order to maintain coherence. Indeed, as Chakrabarti noted, it is vital to Śaṃkara’s entire project that there be a difference between the plurality of the world and an “unpresentable impossibility.”

As seen above, on textural grounds, Śaṃkara cannot deny the premise that at no time is the self truly sad. One might therefore suggest the argument rests on a conflation of ātman and jīva. It appears to my jīva that I am sad, but at no time is my ātman (The Ātman) sad. However, if this objection were made, the argument could just be re-run with the x term being “It appears my ātman is my jīva,” and the contradiction could be produced again.

Another tactic to defuse the contradiction is to suggest that perhaps it only seems to coherently appear to us that we are sometimes sad due to ignorant superimposition, but it does not actually appear to us. However, normally, we think of ourselves as having privileged access to knowledge about our selves and their internal states, such that we can never doubt or be wrong about what appears to us. From various passages,†Eg. Brahmasūtrabhāṣya, II.ii.25, “the conscious subject never has any doubt whether it is itself or only similar to itself,” and II.i.14, “The man who has risen from sleep […] does not on that account consider the consciousness he had of them to be unreal likewise.” it is clear that Śaṃkara would also accept a well-formulated claim of personal indubitability. At the same time, however, there is ground to say that on an Advaitin account our first person current mental state beliefs are (almost) never correct, since they attribute various temporal states to the eternal, unchanging consciousness. William Alston in “Varieties of Privileged Access” divides indubitability into three categories — ”logical impossibility of entertaining a doubt, psychological impossibility of entertaining a doubt, [and] impossibility of their being any grounds for doubt”†Alston, p. 226. — and argues quite cogently that the first two kinds of indubitability are only of epistemic import when they entail the “normative indubitability” of the third category. The matter at hand is whether there can be a ground, and the absence of doubt is only a mark of groundlessness. On this basis, Alston eventually defines thirty-four different possible ways to cash out the “self-warrant” claim for first person current mental state beliefs. For our purposes, perhaps the most useful is such beliefs are “always warranted in normal conditions.”†Ibid., p. 240. Such a definition coheres with the Advaita theory of svataḥprāmāṇyavāda, under which, as Deutsch describes it, “An idea is held to be true or valid, then, the moment it is entertained […] until it is contradicted in experience or is shown to be based on defective apprehension.”†Deutsch, p. 86. Of course, the difficulty is in defining “normal conditions,” since it “normally” seems that it appears to me that my self has a body, emotions, temporal states, etc. However, it also normally seems to appear that the steps in “Ascending and Descending” are continuously rising. Perhaps, as in that case, the mark of the conditions of warrant is totality. However, is it possible that first person current mental state beliefs could lack “the conditions of place, time, and cause, and the circumstance of non-refutation”? To explore this possibility, we must look at the case of living enlightenment, jīvan-mukti.

Śaṃkara repeatedly emphasizes that enlightenment cannot come about as a matter of religious work (karma). Nor, as in many forms of Protestant Christianity, is salvation purely a matter of faith. Moreover, we have already seen that Śaṃkara dismisses the idea that enlightenment can be achieved through reasoning. In the end, “the entire body of regular rites […] serves as a means to liberation through the attainment of Self-knowledge.”†Bṛhadāraṇyakopaniṣadbhāṣya, IV.iv.22, p. 755. P. George Victor summarizes,

According to Śaṃkara, action helps one to get purification of mind and leads to the knowledge of Brahman through renunciation. So it is indirectly but not directly an aid to liberation.†Victor, p.137.

Enlightenment is nothing other than the removal of ignorance and seeing the true nature of the self. However, the nature of ignorance makes it incompatible with knowledge and thus inexplicable and not subject to removal by rational argument. Deutsch explains,

Knowledge destroys ignorance, hence from the standpoint of knowledge, there is no ignorance whose origin stands in question. And when in ignorance, one cannot […] describe the process by which this ignorance ontologically comes to be.

The Advaitin thus finds himself in avidyā; he seeks to understand its nature, to describe its operation, and to overcome it: he cannot tell us why it, or the mental processes which constitute it, is there in the first place. With respect to its ontological source, avidyā must be necessarily unintelligible.†Deutsch, p. 85.

Since ignorance is so pervasive in our ordinary experience, it limits our field of possible experiences in both a negative and positive sense. On the negative side, ignorance is a lack of awareness, but on the positive side, it creates the framework in which the pramāṇas operate. Again, Deutsch summarizes the Advaitin argument,

“To know” requires self-consciousness […] The self cannot, on this level of its being, ever fully grasp itself as a subject apart from objects or objects apart from the self as a subject. […] A realistic epistemology is thus philosophically necessary but ultimately false. It is restricted only to a portion of human existence.†Deutsch, p. 97.

To return to Boardman’s argument, “to dream of someone’s squaring the circle is to dream of something which, in the dream, is acknowledged by all to have been the squaring of the circle.”†Boardman, pp. 224–225 In the same way, for Śaṃkara, to know something through the pramāṇas is to know something which, in ordinary experience, will not be contradicted by a further experience. Certain forms of such knowledge, like the evidence of first person current mental state beliefs, will be “always warranted in normal conditions,” but normal conditions are not the only conditions. Śaṃkara explicitly uses the language of the dream to explain how the limited scope of the pramāṇas is accounted for by his theory.

Other objections are started. — If we acquiesce in the doctrine of absolute unity, the ordinary means of right knowledge, perception, &c., become invalid because the absence of manifoldness deprives them of their objects; just as the idea of a man becomes invalid after the right idea of the post (which at first had been mistaken for a man) has presented itself. […]

These objections, we reply, do not damage our position because the entire complex of phenomenal existence is considered as true as long as the knowledge of Brahman being the Self of all has not arisen; just as the phantoms of a dream are considered to be true until the sleeper wakes.†Brahmasūtrabhāṣya, II.i.14.

Thus, when Hume asks, “Now ‘tis certain we have an idea of extension [and other conceivables]; for otherwise why do we talk and reason concerning it?” Śaṃkara has answer: Because it is pragmatically useful in the domain of ignorance of the true nature of the self.

The emptiness of the pramāṇas also explains why it is that reasoning alone is insufficient for enlightenment. Because the pramāṇas are the means of knowing under the assumption of a subject-object duality, there is no way that the pramāṇas themselves would be able to undermine that duality and reveal the non-dual nature of the self. Ram-Prasad takes this as the moral of the dream cognition for Śaṃkara, not that everything might not be external as the Yogācārins take it, but that what seems now to be a coherent appearance may in fact turn out not to be:

Invalidation, as of dream cognition, is possible only because there is a system of validation, and the system of validation is available only because of the content of waking experience.†“Dream and Reality,” p. 439

Ram-Prasad further argues elsewhere that,

no knowledge-claim which can meet the standard of the pramāṇas allows us to claim that what is currently experienced can never be invalidated. […] The system of validation is legitimately applicable so long as that to which it is applied is the very same experienced world from which the system’s authority is derived. Since pramāṇa theory is understood as being about the world […], the legitimacy of theory is limited to the currently experienced world.†Advaita Epistemology and Metaphysics, p. 90. This argument reminds us of Hilary Putnam’s in “Brains in a vat” that we cannot be brains in a vat, since what the word “vat” refers to cannot be outside of the world we are in. In the same way, pramāṇa theory cannot refer to what is beyond it. Ram-Prasad’s own formulation deliberately parallels Kant’s argument concerning the noumena.

With this background in place, we can also see how Śaṃkara’s maxim naturally falls out of the metaphysical system he establishes. If the ordinary pramāṇas are the arbiter of what it is possible to perceive in totality in usual experience, then it is natural to suggest that these pramāṇas are not capable of presenting what is impossible. As we have quoted Śaṃkara’s before, “Possible is whatever is apprehended by perception or some other means of proof; impossible is what is not so apprehended.”†Brahmasūtrabhāṣya, II.ii.28. Thus, while not a wholly analytical truth, the maxim is a natural corollary to the rest of the system Śaṃkara presents. To return to Alston’s classifications, what cannot be doubted by ordinary psychology also cannot have a ground for doubt, since the existence of a ground depends upon the ability of the ground to be known through a pramāṇa.

To return to the central question of the contradiction of Śaṃkara’s maxim, since I am still mired in ignorance, I do not yet have grounds to deny premise one. However, since I am not enlightened, I also do not yet have the basis to say that I know premise two either, since it cannot be known apart from enlightenment, only trusted through faith in the Vedas. If I were to become enlightened, then premise two would arise and premise one would fall away, and so the contradiction would dissolve.

The only remain question is whether his position as reconstructed can still bear the weight against the Yogācārins that Śaṃkara wants it to without self-dealing. Whether or not Śaṃkara is being fair to the full range of possible Yogācārin counter-arguments, his argument against them can be constructed like so: If the Yogācārins are using a Diodoran notion of impossibility, then they will want to argue that an external world is impossible, since it at no time exists.†Vasubandhu also argues explicitly for the impossibility of the external world in the Viṃśatikā, but I am not attempting to give a full portrait of the Yogācārin position here. However, doing so contradicts Śaṃkara’s maxim as in the formalization above, since even the Yogācārins admit that it appears as though an external world exists. However, unlike Śaṃkara, they cannot beg off the contradiction by temporarily denying premises (other than the maxim), since it is through the ordinary pramāṇa that the non-externality of the world is conceived and not through some extraordinary pramāṇa like self-knowledge.†There may still be other ways for the Yogācārins to wriggle out of the contradiction, but this is what Śaṃkara takes their problem to be.

Śaṃkara’s core conflict with Yogācārins is that they use the pramāṇas of inference and perception in order to build a chain of reasoning that shows that it is impossible for there to be an external world, but such a claim could never be confirmed, since it conflicts so sharply with the ordinary findings of the pramāṇas. Hence Śaṃkara’s claim that, “we certainly cannot allow would-be philosophers to deny the truth of what is directly evident to themselves.”†Ibid., II.ii.29. The difficulty for the Yogācārins is that they claim both that it is impossible for there to be an external world and that it appears that there is one. Śaṃkara does not claim that it appears that the self is one, since this is known only in enlightenment. The Yogācārins, however, have claimed that through reasoning we can know that the external world is impossible, which means that the contradiction derived above can be run against their system. Their fundamental problem is that they need to show that the external world is impossible — since otherwise the dream example would give no traction to their theory as it only proves the possibility of being mistaken about the externality of experience not the impossibility of externality — but within the realm of the ordinary pramāṇas, there is no evidence that can overturn a common verdict of the senses. However, by the same token, there can be no evidence about what may be the case according to an extraordinary pramāṇa, hence Śaṃkara is safe in his claim that the self is non-dual and this is not to be proven by any source other than self-knowledge which is cultivated on the basis of the Vedas but ultimately transcends them. Hence his denials are not couched at the level of ordinary experience or meant to overturn common sense, but only to lead us toward true, ultimate-level knowledge of the self. Hence, Śaṃkara is able to withstand the blunt charge of contradiction through the emphasis of the subtleties of his system.†Another possibility, not explored here, is to construct a notion of possibility more foreign to Śaṃkara, but which can nevertheless support the non-dualist position. In such a system, “possible” might mean “possible in some world if subject-object duality were real” or something similar.

Has Śaṃkara managed to defend both his maxim and his metaphysics successfully? Based on our investigation, we have seen that Śaṃkara’s system can be interpreted coherently. However, his system still has the problem that for those who do not accept the authority of the Vedas, the non-duality of the self cannot be rationally shown to be the case. Śaṃkara’s only claims that it cannot rationally be ruled out, a kind of Fideist position. Similarly, as we have interpreted it, Śaṃkara’s maxim is not a tautological claim but one with strong intuitive support and a central position within the framework of Advaitin metaphysics. As such, the further burden is on the Advaitin to demonstrate through their lives that the Vedas are true and enlightenment is a goal really worth pursuing. We must be given reason to hope if not know.

Alston, William. “Varieties of Privileged Access” in American Philosophical Quarterly. Vol. 8, No. 3 (1971), pp. 223–241.

Boardman, William S. “Dreams, Dramas, and Scepticism” in The Philosophical Quarterly,

Vol. 29, No. 116 (July 1979), pp. 220–228. Online at <http://www.jstor.org/stable/2218818> as of December 2008.

Chakrabarti, Arindam. “Metaphysics in India” in A Companion to Metaphysics. Eds. Jaegwon Kim and Ernest Sosa. Blackwell, 1995. Pp. 318–323.

———. “Rationality in Indian Philosophy” in A Companion to World Philosophies. Eds. Eliot Deutsch and Ronald Bontekoe. Blackwell Publishing, 1999. Pp. 259–278.

Cresswel, M. J. “A Highly Impossible Scene” in Meaning, Use, and Interpretation of Language. Eds. Ranier Bäuerle, Christoph Schwarze, and Arnim von Stechow. Walter de Gruyter & Co., Berlin, 1983. Pp. 62–78.

Deutsch, Eliot. Advaita Vedānta: A Philosophical Reconstruction. First ed. East-West Center Press, Honolulu, 1969.

Hume, David. A Treatise of Human Nature: Being an Attempt to introduce the experimental Method of Reasoning into Moral Subjects. Original 1740. Online at <http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/4705> as of December 2008.

Kant, Immanuel. Critique of Pure Reason. Trans. Werner S. Pluhar. Hackett Publishing Co., Indianapolis. Originals 1781, 1787; translation 1996.

Matilal, Bimal. Logical and Ethical Issues of Religious Belief. University of Calcutta, 1982.

Perrett, Roy. “Is Whatever Exists Knowable and Nameable?” inPhilosophy East & West, Vol. 49, No. 4 (October 1999). Pp. 401–414.

———. “Truth, Relativism, and Western Conceptions of Indian Philosophy” in Asian Philosophy, Vol. 8, No. 1 (1998), pp. 19–29. Online at <http://www.informaworld.com/10.1080/09552369808575469> as of December 2008.

Priest, Graham. “Perceiving Contradictions” in Australasian Journal of Philosophy, Vol. 77, No. 4 (1999), pp. 439–446. Online at <http://www.informaworld.com/10.1080/00048409912349211> as of December 2008.

Prior, Arthur. “Diodoran Modalities” in The Philosophical Quarterly, Vol. 5, No. 20 (July 1955), pp. 205–213. Online at <http://www.jstor.org/stable/2957434> as of December 2008.

Putnam, Hilary. “Brains in a vat” in Truth, and History. Cambridge University Press, 1982. Pp. 1–21. Online at <http://www.cavehill.uwi.edu/bnccde/ph29a/putnam.html> as of December 2008.

Ram-Prasad, Chakravarthi. Advaita Epistemology and Metaphysics: An Outline of Indian Non-Realism. RoutledgeCurzon, London, 2002.

———. “Dreams and Reality: The Śaṅkarite Critique of Vijñānavāda” in Philosophy East & West. Vol. 43 No. 3 (Jul 1993). Pp. 405–456.

Śaṃkara. Bhagavadgītābhāṣya, as excerpted in A Source Book of Advaita Vedānta. Eds. Eliot Deutsch and J. A. B. Buiten. Trans. A. Mahādeva Śāstri. University Press of Hawaii, 1971.

———. Brahmasūtrabhāṣya, as translated as The Vedanta Sutras, With the Commentary by

Saṅkarâkârya by George Thibaut, 1890. Online at <http://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/sbe34/> as of December 2008.

———. Bṛhadāraṇyakopaniṣadbhāṣya, as translated as The Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad with the Commentary of Śankarācārya by Swāmī Mādhavānanda. Third ed. Advaita Ashram, Mayavaii, 1950.

Sorensen, Roy. “Art of the Impossible” in Imagination, Conceivability, Possibility. Eds. Tamar Gendler and John Hawthorne. Oxford University Press, 2002. Pp. 337-368.

Victor, P. George. Social Philosophy of Vedānta. K P Bagchi & Co., Calcutta, 1991.

Williams, Paul. “On the Abhidharma Ontology” in Journal of Indian Philosophy. Vol. 9, No. 3 (September 1981). Pp. 227–257.